Sorry... Cosmix was built as a web design demo site.

You can view the Home page, Blog Page, and/or read blog posts.

The About, Contact, and Learn More links are just filler content.

Sorry... Cosmix was built as a web design demo site.

You can view the Home page, Blog Page, and/or read blog posts.

The About, Contact, and Learn More links are just filler content.

For centuries, our understanding of the cosmos has been shaped by what we can see, from the starlight captured by our eyes to the radio waves detected by massive satellite dishes.

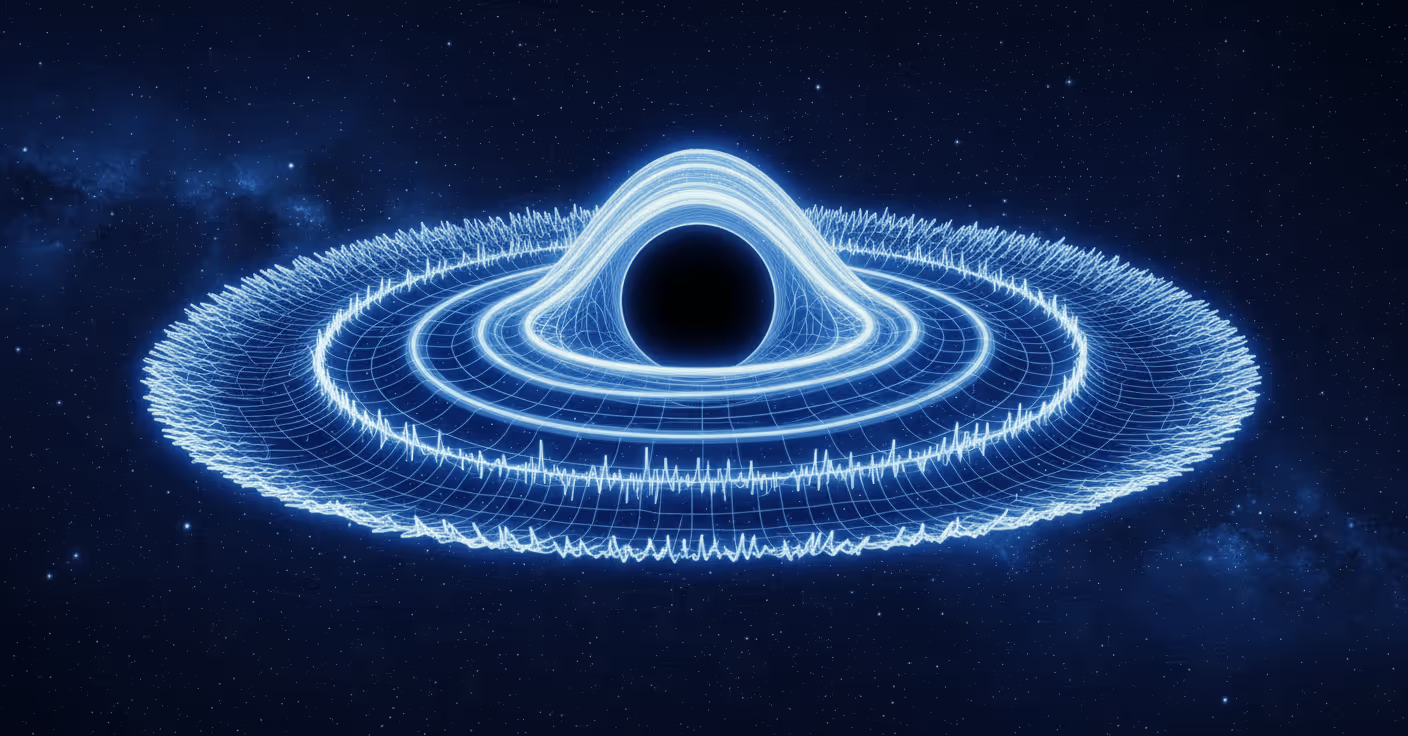

But what if we could listen to the universe? What sounds would a black hole collision make, or the spiraling death dance of two neutron stars?

Thanks to a groundbreaking discovery in 2015, we now can. We've opened a new window into the cosmos by detecting gravitational waves, ripples in the fabric of spacetime itself.

The story of gravitational waves begins with Albert Einstein's theory of General Relativity, published in 1915. Einstein proposed that space and time are not separate, but are interwoven into a four-dimensional tapestry called spacetime.

He theorized that massive objects, like stars and planets, curve this fabric, and we experience this curvature as gravity. His theory also predicted that accelerating masses, such as two black holes spiraling towards each other, would create ripples that travel outward at the speed of light.

However, Einstein himself believed these waves would be far too weak to ever be detected. For nearly a century, gravitational waves remained a beautiful, but unproven, consequence of his theory.

The challenge of detecting these infinitesimal ripples was immense. A gravitational wave passing through Earth would stretch and squeeze everything by an amount less than the width of a single atom.

To "hear" these waves, scientists needed a truly audacious instrument. Enter the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).

LIGO consists of two identical detectors, one in Livingston, Louisiana, and another in Hanford, Washington, separated by over 3,000 kilometers. Each detector is an L-shaped instrument with two 4-kilometer-long arms.

Inside, a laser beam is split and sent down each arm, bouncing off mirrors at the end and returning to a detector. If a gravitational wave passes through, it will slightly stretch one arm while squeezing the other.

This tiny change in length causes the two laser beams to arrive back at the detector out of sync, creating an interference pattern that reveals the presence of the wave. The two detectors work in tandem, allowing scientists to confirm a signal and pinpoint its direction.

On September 14, 2015, LIGO made history. The two detectors simultaneously registered a signal, a "chirp" that lasted for a fraction of a second.

This wasn't just a random blip; it was the exact pattern predicted by Einstein's equations for two colliding black holes. The signal originated from the merger of two black holes, one 36 times the mass of our sun and the other 29 times.

In that final moment, they combined to form a new, 62-solar-mass black hole, releasing the remaining 3 solar masses as pure energy in the form of gravitational waves.

This discovery, for which the founders of LIGO were awarded the Nobel Prize, confirmed a century-old prediction and validated a whole new way of observing the universe.

Since that first detection, LIGO and its partner observatories, Virgo in Italy and KAGRA in Japan, have detected dozens of gravitational wave events, including:

Gravitational wave astronomy is still in its infancy, but it promises to revolutionize our understanding of the universe.

It allows us to explore the most violent and extreme events in the cosmos that are invisible to our eyes, from the birth of black holes to the potential secrets of the universe's origin.

We are no longer just looking at the cosmos; we are listening to its echoes.